Babishvili

Czech politics have come to resemble again the politics of another former Soviet satellite.

It has taken a quarter of a century. But thanks to Vaclav Klaus, Milos Zeman and Miroslav Kalousek, Czech politics have come to resemble again the politics of another former Soviet satellite - Georgia.

On October 25, 2012, a reclusive oligarch called Bidzina Ivanishvili swept to power on the back of his own lavishly funded political movement called Georgian Dream.

This coming Friday, exactly one year after a billionaire became the prime minister of Georgia, voters in the Czech Republic will be deciding if they want their own version of Ivanishvili to lead them.

To compare Andrej Babis to Bidzina Ivanishvili is not to derogate either: it is to acknowledge that each appeals to his own voters in the same way. Their appeal is based upon the loss of faith in political parties and the hope that a strong leader will end abuse.

This is a desperate hope. It reveals how fragile the popular attachment to parliamentary democracy can become when a political elite persists in its greed and stupidity.

The statement, “But Babis cannot be any worse!”, is a plea, not a conclusion. Babis can be much better or much worse or just the same. But it all depends upon Babis – not you. And this is the source of his appeal, the appeal of a leader who will solve our problems for us.

After a year as prime minister, Bidzina Ivanishvili has announced that he will appoint a new prime minister this month, and step into the background. “I won’t be a politician any more”, he states.

A retreat from politics is not a retreat from power. History is littered with dictators that held no formal position in the constitution of their country. Once we become dependent on a strong leader, rather than on institutions, politics becomes an entirely arbitrary affair.

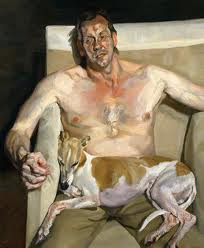

His painting, Eli and David, 2005, by Lucian Freud, in full

It has taken a quarter of a century. But thanks to Vaclav Klaus, Milos Zeman and Miroslav Kalousek, Czech politics have come to resemble again the politics of another former Soviet satellite - Georgia.

On October 25, 2012, a reclusive oligarch called Bidzina Ivanishvili swept to power on the back of his own lavishly funded political movement called Georgian Dream.

This coming Friday, exactly one year after a billionaire became the prime minister of Georgia, voters in the Czech Republic will be deciding if they want their own version of Ivanishvili to lead them.

To compare Andrej Babis to Bidzina Ivanishvili is not to derogate either: it is to acknowledge that each appeals to his own voters in the same way. Their appeal is based upon the loss of faith in political parties and the hope that a strong leader will end abuse.

This is a desperate hope. It reveals how fragile the popular attachment to parliamentary democracy can become when a political elite persists in its greed and stupidity.

The statement, “But Babis cannot be any worse!”, is a plea, not a conclusion. Babis can be much better or much worse or just the same. But it all depends upon Babis – not you. And this is the source of his appeal, the appeal of a leader who will solve our problems for us.

After a year as prime minister, Bidzina Ivanishvili has announced that he will appoint a new prime minister this month, and step into the background. “I won’t be a politician any more”, he states.

A retreat from politics is not a retreat from power. History is littered with dictators that held no formal position in the constitution of their country. Once we become dependent on a strong leader, rather than on institutions, politics becomes an entirely arbitrary affair.

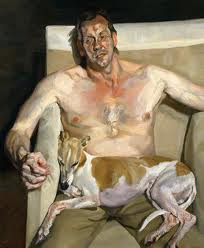

His painting, Eli and David, 2005, by Lucian Freud, in full

Miluji cla! Donald Trump a jeho životní láska

Miluji cla! Donald Trump a jeho životní láska Finský prezident má recept na Trumpa. Golfovou diplomacii!

Finský prezident má recept na Trumpa. Golfovou diplomacii! Ukrajinská svatba online: rychlý válečný obřad bez příkras i bez příloh

Ukrajinská svatba online: rychlý válečný obřad bez příkras i bez příloh Z deníku dobrovolníka: Nebezpečná cesta za velitelkou Runou

Z deníku dobrovolníka: Nebezpečná cesta za velitelkou Runou Týden v Česku: Bendova pravda, Babišovo kafe a Pavlovo pózování

Týden v Česku: Bendova pravda, Babišovo kafe a Pavlovo pózování