Made in Switzerland: origins of a Czechoslovak oligarch

Is Andrej Babis the best capital investment ever made by Czechoslovak Communist counter-intelligence?

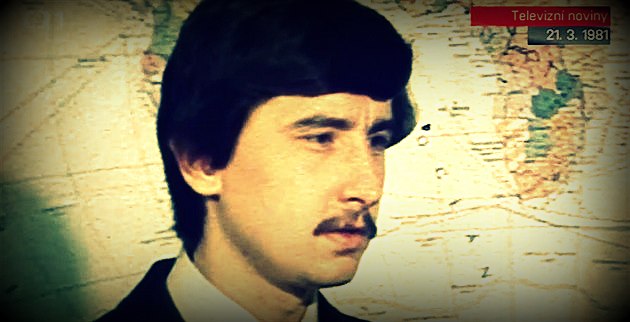

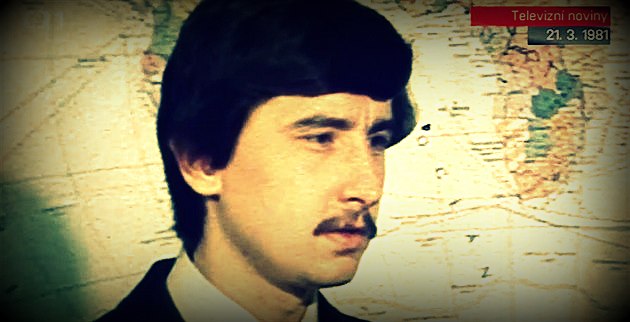

The world not yet his oyster: Andrej Babis on Communist TV at the tender age of 27. Three decades later, he is set to become the Czech prime minister.

It is now understood how the Communist state security services began redistributing state-owned property to themselves before 1989, and how the arrival of democracy accelerated an informal privatisation process already well underway. See here

Large capital sums, deposited by the security services in businesses and banks in the West long before the Communists lost power, were brought home in the first half of the 1990s and used to acquire state firms now up for sale.

Is Andrej Babis a beneficiary of this process, an example of how the Czechoslovak Communist state security apparatus helped to create oligarchs from among those it trusted, using funds squirrelled out of the country before 1989?

In an earlier post here, I looked at how Andrej Babis has surrounded himself with senior police detectives and Communist counter-intelligence agents, in both his business and his political movement. One reason for his preference for such people might be that he had little choice in the matter.

For fifteen years, Andrej Babis was employed in state-owned Petrimex, the monopoly importer of oil and chemical products to Slovakia. By 1993, he was on the board. In that same year, Petrimex established its Agrofert subsidiary. But it was not until 1995 that Babis made his big move, turning himself, from an employee of a state firm with close ties to the state security services, into an oligarch.

An obscure Swiss entity called Ost Finanz und Investition (hereafter referred to as OF&I) quietly re-capitalised Agrofert in 1994, and in this way seized control of the business from Petrimex. Where the Swiss company got hold of the funds to dilute Petrimex's stake remains unclear. All Babis has been willing to say is that the money came from his "Swiss schoolmates, who wanted to earn some money, so I helped them." Babis' father was a Czechoslovak official at the United Nations in Geneva, and Andrej went to College Rousseau, a grammar school in the city.

Readers will recall how, in March 2014, the Czech finance minister used a government press conference to threaten the owner of ECHO24, a Czech news server, by wondering aloud whether he had sufficient legally declared wealth to cover the costs of running such an enterprise.

Exactly the same doubts should have been raised about Babis himself at government press conferences in the period 1995 - 2002, as Agrofert used OF&I over and over again to acquire assets from the Czech state (Lovochemie and Aliachem, for example).

No official doubts were ever raised however, despite warnings from the Czech secret service at the time that OF&I was possibly a vehicle to hide the investments of a third party acting on the orders of the Russian state. These intelligence warnings were ignored, and the government of Milos Zeman went ahead and sold a majority stake in Unipetrol to Agrofert in 2001.

Even Babis recognised that the ‘Swiss schoolmates’ story would not wash with an asset as strategic as Unipetrol. A more credible vehicle was needed. Just before the Unipetrol bids closed in late 2001, OF&I sold its stake in Agrofert to Swiss fertiliser trader, Ameropa. See here

Attempts at the time to establish who actually owned Ameropa were as unrewarding as those to establish who owned OF&I, even though, in the case of Ameropa, the firm claimed to employ 600 people across three continents (today, it claims to employ 5000 people across five continents).

It turned out that no one, not even the Czech ministers who approved the Unipetrol sale to Agrofert in 2001, knew anything about Agrofert’s second Swiss owner. And however many employees across however many continents it boasted, not even Ameropa was flush enough to raise the EUR 360 million Agrofert offered for a 63% stake in Unipetrol. The sale was abandoned and two years later, Unipetrol was sold to PKN Orlen.

Today, Ameropa is managed by one of Babis’ closest confidants, Jan Kadanik, director for strategy and finance at Agrofert in 2001 – 2007. Kadanik started running Ameropa in 2007, at least, that is when Kadanik formally started running Ameropa.

Given what we now know about Babis' long-standing relations with retired Communist counter-intelligence officers like Libor Siroky, who chairs Agrofert’s supervisory board, and Radmila Kleslova, who chairs the Prague chapter of ANO 2011, it seems just as possible that Babis’ 'Swiss schoolmates' were in fact sitting on funds removed from Communist Czechoslovakia before 1989, waiting for the right moment to send them home again.

Why are we not sure? How is it that so little is known about the origins of the capital of a man who has acquired so many assets from the Czech state; of a man who today, as finance minister, has acquired control over large parts of Czech politics; and of a man who tomorrow may well be the Czech prime minister?

Is it not about time that a thorough investigation into the origins of Babis' capital was made by the state in the interests of its own national security? Or is such an investigation even possible now that Andrej Babis is the single most powerful politician by far in the Czech Republic?

The world not yet his oyster: Andrej Babis on Communist TV at the tender age of 27. Three decades later, he is set to become the Czech prime minister.

It is now understood how the Communist state security services began redistributing state-owned property to themselves before 1989, and how the arrival of democracy accelerated an informal privatisation process already well underway. See here

Large capital sums, deposited by the security services in businesses and banks in the West long before the Communists lost power, were brought home in the first half of the 1990s and used to acquire state firms now up for sale.

Is Andrej Babis a beneficiary of this process, an example of how the Czechoslovak Communist state security apparatus helped to create oligarchs from among those it trusted, using funds squirrelled out of the country before 1989?

In an earlier post here, I looked at how Andrej Babis has surrounded himself with senior police detectives and Communist counter-intelligence agents, in both his business and his political movement. One reason for his preference for such people might be that he had little choice in the matter.

For fifteen years, Andrej Babis was employed in state-owned Petrimex, the monopoly importer of oil and chemical products to Slovakia. By 1993, he was on the board. In that same year, Petrimex established its Agrofert subsidiary. But it was not until 1995 that Babis made his big move, turning himself, from an employee of a state firm with close ties to the state security services, into an oligarch.

An obscure Swiss entity called Ost Finanz und Investition (hereafter referred to as OF&I) quietly re-capitalised Agrofert in 1994, and in this way seized control of the business from Petrimex. Where the Swiss company got hold of the funds to dilute Petrimex's stake remains unclear. All Babis has been willing to say is that the money came from his "Swiss schoolmates, who wanted to earn some money, so I helped them." Babis' father was a Czechoslovak official at the United Nations in Geneva, and Andrej went to College Rousseau, a grammar school in the city.

Readers will recall how, in March 2014, the Czech finance minister used a government press conference to threaten the owner of ECHO24, a Czech news server, by wondering aloud whether he had sufficient legally declared wealth to cover the costs of running such an enterprise.

Exactly the same doubts should have been raised about Babis himself at government press conferences in the period 1995 - 2002, as Agrofert used OF&I over and over again to acquire assets from the Czech state (Lovochemie and Aliachem, for example).

No official doubts were ever raised however, despite warnings from the Czech secret service at the time that OF&I was possibly a vehicle to hide the investments of a third party acting on the orders of the Russian state. These intelligence warnings were ignored, and the government of Milos Zeman went ahead and sold a majority stake in Unipetrol to Agrofert in 2001.

Even Babis recognised that the ‘Swiss schoolmates’ story would not wash with an asset as strategic as Unipetrol. A more credible vehicle was needed. Just before the Unipetrol bids closed in late 2001, OF&I sold its stake in Agrofert to Swiss fertiliser trader, Ameropa. See here

Attempts at the time to establish who actually owned Ameropa were as unrewarding as those to establish who owned OF&I, even though, in the case of Ameropa, the firm claimed to employ 600 people across three continents (today, it claims to employ 5000 people across five continents).

It turned out that no one, not even the Czech ministers who approved the Unipetrol sale to Agrofert in 2001, knew anything about Agrofert’s second Swiss owner. And however many employees across however many continents it boasted, not even Ameropa was flush enough to raise the EUR 360 million Agrofert offered for a 63% stake in Unipetrol. The sale was abandoned and two years later, Unipetrol was sold to PKN Orlen.

Today, Ameropa is managed by one of Babis’ closest confidants, Jan Kadanik, director for strategy and finance at Agrofert in 2001 – 2007. Kadanik started running Ameropa in 2007, at least, that is when Kadanik formally started running Ameropa.

Given what we now know about Babis' long-standing relations with retired Communist counter-intelligence officers like Libor Siroky, who chairs Agrofert’s supervisory board, and Radmila Kleslova, who chairs the Prague chapter of ANO 2011, it seems just as possible that Babis’ 'Swiss schoolmates' were in fact sitting on funds removed from Communist Czechoslovakia before 1989, waiting for the right moment to send them home again.

Why are we not sure? How is it that so little is known about the origins of the capital of a man who has acquired so many assets from the Czech state; of a man who today, as finance minister, has acquired control over large parts of Czech politics; and of a man who tomorrow may well be the Czech prime minister?

Is it not about time that a thorough investigation into the origins of Babis' capital was made by the state in the interests of its own national security? Or is such an investigation even possible now that Andrej Babis is the single most powerful politician by far in the Czech Republic?

Miluji cla! Donald Trump a jeho životní láska

Miluji cla! Donald Trump a jeho životní láska Finský prezident má recept na Trumpa. Golfovou diplomacii!

Finský prezident má recept na Trumpa. Golfovou diplomacii! Ukrajinská svatba online: rychlý válečný obřad bez příkras i bez příloh

Ukrajinská svatba online: rychlý válečný obřad bez příkras i bez příloh Z deníku dobrovolníka: Nebezpečná cesta za velitelkou Runou

Z deníku dobrovolníka: Nebezpečná cesta za velitelkou Runou Týden v Česku: Bendova pravda, Babišovo kafe a Pavlovo pózování

Týden v Česku: Bendova pravda, Babišovo kafe a Pavlovo pózování