Why Babiš should be prime minister

And why his disputed StB record is his trump card, preventing him but not his people from entering the government - an ideal outcome for him.

This is not absurd: It is democratic politics.

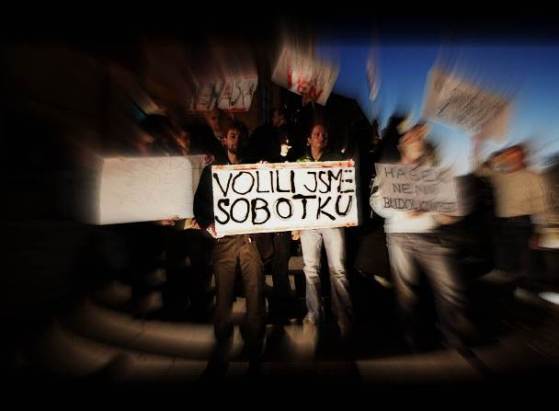

Now that Michal Hasek and his putschists have been safely dealt with, Andrej Babis has boldly rallied behind Bohuslav Sobotka. Babis insists that ANO will go into government with CSSD and KDU-CSL on the condition that Sobotka be prime minister. Apparently, Babis does not have the stomach "to work with a liar" (in which case, you will say, he will soon be out of work in politics.)

But there is at least one serious reason why Babis wants Sobotka - and not himself - to be prime minister, and why Sobotka and KDU-CSL's chairman, Pavel Belobradek, should insist on him taking the top job in a coalition government in which they too would participate.

The reason is the nature of power itself.

There is only one thing more insidious than the exercise of power and that is the exercise of power without responsibility. Or as the nineteenth century British historian, Lord Acton, observed, ‘power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.’

Erik Best hit the nail on the head in his Final Word column when he argued that, from “the standpoint of public control, it is much better that Babis become the Czech prime minister than chairman of the budget committee”. Exactly.

My principal objection to Andrej Babis the politician is not his dubious past or his threat to run the country as efficiently as he runs Agrofert. It is the great potential he enjoys to avoid responsibility.

Politicians at all times and in all places are corruptible, and without robust institutions and attentive citizens, all are corrupt. But only some are efficient. This is why an inefficient politician that can be held to account is still much preferable to an efficient politician that cannot.

I do not believe that ANO can avoid going into government. Nor do I believe that Babis in fact wants ANO to avoid going into government. But there are good reasons why Babis himself is reluctant to hold high political office. These can be reduced to four: his character, his business, his political movement and his coalition partners.

First, there is his character. By all accounts, Babis is not an especially vain man. His desire for power seems stronger than his love of praise. In this, he is quite unlike Vaclav Klaus for example, who evidently gets more excited by the praise that power brings with it than the power itself. Babis appears more like Livia Klaus, who obviously relishes in power for its own sake (it is said that she has enough ambition for both herself and her husband.) In short, Babis does not appear to need to surround himself with sychophants (sic) and the trappings of high office. He is content to wield power discretely, from behind, like Mrs. Klaus.

Second, there is his business. We must assume that Babis’s business matters more to him than anything else apart from his family. Most self-made men are defined by the companies they have built from nothing. The conflicts of interest that would engulf the absolute owner of Agrofert if he were to become a government minister (unless he was to become the minister of culture) can be avoided, or at least more easily managed (or disguised) if he were to remain on the backbenches.

Third, there is his political movement. ANO 2011 is not a political machine, at least not yet. To turn this collection of ambitious individuals into a broad-based political party will be a most laborious labour of love over many years. If the most talented of the bunch go into government today, that slow work of party building will not get done. And although ANO 2011 cannot now avoid going into government, its owner can. In short, if Babis can leave his business in the hands of his people while he runs the country, then he can just as well leave the country in the hands of his people while he runs his business.

Fourth, there are his coalition partners. If CSSD and KDU-CSL were stronger than they are today, there would be a greater incentive for Babis to become prime minister. But CSSD is busy trying to decide if it wants to be a political party or an appendage of Milos Zeman. And the re-born KDU-CSL is still in its infancy. My point is that instability in CSSD and inexperience in KDU-CSL makes it easier for Babis to avoid becoming a government minister himself.

Babis has called the internal struggle within CSSD ‘an absurd situation’. How so? From the perspective of an absolute owner of a ruthlessly efficient company, I can see that the squabbling of politicians is an ‘absurd’ waste of time. But that is the very stuff of politics, most of which is a waste of time. That is democracy in all its maddening inefficiency.

The absurdity in all this is Babis himself. It is absurd that a self-made Slovak billionaire with a disputed record of collaboration with the StB and a handful of former politicians, some of whom are no doubt well-meaning and others of whom are clearly opportunists, should now be expected to save the Czech democratic system from itself.

Over the last few days, I have made the comparison between Andrej Babis and the Georgian billionaire, Bidzina Ivanishvili. A week ago, after a year as prime minister, Ivanishvili announced that he will replace himself with a new prime minister, and step into the background. “I won’t be a politician any more”, he declares. But Georgian Dream, the party he funds and leads, will still run the government.

A retreat from high political office is not a retreat from power. The world is full of de facto rulers that hold no formal position in the running of their country.

Is the Czech Republic to have such a ruler and to become such a country?

ANO’s future coalition partners should insist that ANO’s owner (and chairman) becomes prime minister. They should refuse to let him orchestrate things from a seat in parliament, or even from a kitchen cabinet in his fancy restaurant on the Cote d’Azur.

In short, Pavel Belobradek and Bohuslav Sobotka must deny Andrej Babis the greatest political luxury of them all, the luxury of power without responsibility. One Milos Zeman is already one too many.

And now we see just how very useful his disputed StB record is for Andrej Babis. It will become his trump card, preventing him, but not his people, from entering the cabinet, whether as prime minister, finance minister or even as minister of culture.

This is not absurd: It is democratic politics.

Now that Michal Hasek and his putschists have been safely dealt with, Andrej Babis has boldly rallied behind Bohuslav Sobotka. Babis insists that ANO will go into government with CSSD and KDU-CSL on the condition that Sobotka be prime minister. Apparently, Babis does not have the stomach "to work with a liar" (in which case, you will say, he will soon be out of work in politics.)

But there is at least one serious reason why Babis wants Sobotka - and not himself - to be prime minister, and why Sobotka and KDU-CSL's chairman, Pavel Belobradek, should insist on him taking the top job in a coalition government in which they too would participate.

The reason is the nature of power itself.

There is only one thing more insidious than the exercise of power and that is the exercise of power without responsibility. Or as the nineteenth century British historian, Lord Acton, observed, ‘power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.’

Erik Best hit the nail on the head in his Final Word column when he argued that, from “the standpoint of public control, it is much better that Babis become the Czech prime minister than chairman of the budget committee”. Exactly.

My principal objection to Andrej Babis the politician is not his dubious past or his threat to run the country as efficiently as he runs Agrofert. It is the great potential he enjoys to avoid responsibility.

Politicians at all times and in all places are corruptible, and without robust institutions and attentive citizens, all are corrupt. But only some are efficient. This is why an inefficient politician that can be held to account is still much preferable to an efficient politician that cannot.

I do not believe that ANO can avoid going into government. Nor do I believe that Babis in fact wants ANO to avoid going into government. But there are good reasons why Babis himself is reluctant to hold high political office. These can be reduced to four: his character, his business, his political movement and his coalition partners.

First, there is his character. By all accounts, Babis is not an especially vain man. His desire for power seems stronger than his love of praise. In this, he is quite unlike Vaclav Klaus for example, who evidently gets more excited by the praise that power brings with it than the power itself. Babis appears more like Livia Klaus, who obviously relishes in power for its own sake (it is said that she has enough ambition for both herself and her husband.) In short, Babis does not appear to need to surround himself with sychophants (sic) and the trappings of high office. He is content to wield power discretely, from behind, like Mrs. Klaus.

Second, there is his business. We must assume that Babis’s business matters more to him than anything else apart from his family. Most self-made men are defined by the companies they have built from nothing. The conflicts of interest that would engulf the absolute owner of Agrofert if he were to become a government minister (unless he was to become the minister of culture) can be avoided, or at least more easily managed (or disguised) if he were to remain on the backbenches.

Third, there is his political movement. ANO 2011 is not a political machine, at least not yet. To turn this collection of ambitious individuals into a broad-based political party will be a most laborious labour of love over many years. If the most talented of the bunch go into government today, that slow work of party building will not get done. And although ANO 2011 cannot now avoid going into government, its owner can. In short, if Babis can leave his business in the hands of his people while he runs the country, then he can just as well leave the country in the hands of his people while he runs his business.

Fourth, there are his coalition partners. If CSSD and KDU-CSL were stronger than they are today, there would be a greater incentive for Babis to become prime minister. But CSSD is busy trying to decide if it wants to be a political party or an appendage of Milos Zeman. And the re-born KDU-CSL is still in its infancy. My point is that instability in CSSD and inexperience in KDU-CSL makes it easier for Babis to avoid becoming a government minister himself.

Babis has called the internal struggle within CSSD ‘an absurd situation’. How so? From the perspective of an absolute owner of a ruthlessly efficient company, I can see that the squabbling of politicians is an ‘absurd’ waste of time. But that is the very stuff of politics, most of which is a waste of time. That is democracy in all its maddening inefficiency.

The absurdity in all this is Babis himself. It is absurd that a self-made Slovak billionaire with a disputed record of collaboration with the StB and a handful of former politicians, some of whom are no doubt well-meaning and others of whom are clearly opportunists, should now be expected to save the Czech democratic system from itself.

Over the last few days, I have made the comparison between Andrej Babis and the Georgian billionaire, Bidzina Ivanishvili. A week ago, after a year as prime minister, Ivanishvili announced that he will replace himself with a new prime minister, and step into the background. “I won’t be a politician any more”, he declares. But Georgian Dream, the party he funds and leads, will still run the government.

A retreat from high political office is not a retreat from power. The world is full of de facto rulers that hold no formal position in the running of their country.

Is the Czech Republic to have such a ruler and to become such a country?

ANO’s future coalition partners should insist that ANO’s owner (and chairman) becomes prime minister. They should refuse to let him orchestrate things from a seat in parliament, or even from a kitchen cabinet in his fancy restaurant on the Cote d’Azur.

In short, Pavel Belobradek and Bohuslav Sobotka must deny Andrej Babis the greatest political luxury of them all, the luxury of power without responsibility. One Milos Zeman is already one too many.

And now we see just how very useful his disputed StB record is for Andrej Babis. It will become his trump card, preventing him, but not his people, from entering the cabinet, whether as prime minister, finance minister or even as minister of culture.

Miluji cla! Donald Trump a jeho životní láska

Miluji cla! Donald Trump a jeho životní láska Finský prezident má recept na Trumpa. Golfovou diplomacii!

Finský prezident má recept na Trumpa. Golfovou diplomacii! Ukrajinská svatba online: rychlý válečný obřad bez příkras i bez příloh

Ukrajinská svatba online: rychlý válečný obřad bez příkras i bez příloh Z deníku dobrovolníka: Nebezpečná cesta za velitelkou Runou

Z deníku dobrovolníka: Nebezpečná cesta za velitelkou Runou Týden v Česku: Bendova pravda, Babišovo kafe a Pavlovo pózování

Týden v Česku: Bendova pravda, Babišovo kafe a Pavlovo pózování