Choosing nuclear reactors in a Cold War climate

Ukraine has turned the choice between American and Russian reactors into a political act with dangerous repercussions for the Czech Republic.

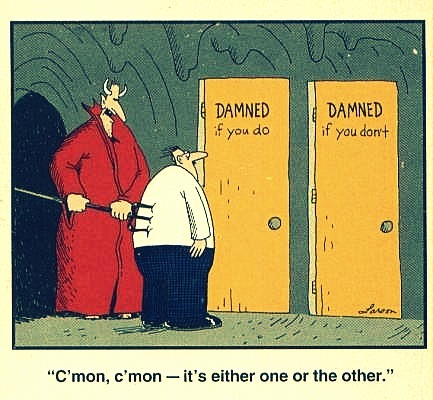

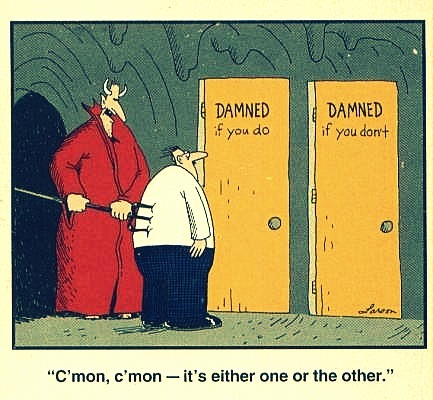

The false choice before you today: American or Russian reactors?

In June 1950, 150 intellectuals from twenty countries gathered in West Berlin to take part in the ‘Congress for Cultural Freedom’, a CIA-funded response to the Communist-backed ‘Congress of the Intellectuals’ staged in the Polish city of Wroclaw two years earlier.

It was classic Cold War stuff. The English historian, Hugh Trevor-Roper, who participated in the Berlin congress, described it as ‘Wroclaw in reverse’. He stood out at the event for his point blank refusal to join in the partisan rant, dismissing the choice between embracing Communism and attacking it as not only false, but foolish as well: if European workers were forced to choose, he argued, they would likely choose Communism.

The ideological trampling upon rational debate is what alarmed Trevor-Roper most about those gatherings of anti-Communist intellectuals, many of them former Communists damaged by their pasts: "After the sterile congresses of Wroclaw and Berlin, I am confirmed in my view that a more satisfactory solution will be offered by those who have never swallowed, and therefore never needed to re-vomit, that obscurantist doctrinal rubbish whose residue can never be fully discharged from the system". (For an account of Trevor-Roper’s participation in the Berlin congress, see Adam Sisman’s biography of the man).

Today, as Washington and Moscow take up their old positions over Ukraine, rational debate is being crushed in the Czech Republic. By far the most significant illustration of this is the issue of who (not whether -that debate was never held here) will build more nuclear reactors in this country.

A year ago, there was still the possibility of making a rational choice between Rosatom and Westinghouse. But since Ukraine collapsed into a proxy war between Russia and the U.S., that possibility has disappeared.

There is no right choice now. It cannot be in the Czech interest to choose between Russia and the U.S. at this time, but if pushed, Prague will go for Rosatom. In either case, the Czechs would be mortgaging a large part of their politics, industry and national budget to one or other of the main combatants in the new Cold War. And in either case, the political fall-out would be considerable.

I can just hear Carl Gershman of the National Endowment for Democracy declaring that, by not choosing the Americans, the Czechs have abandoned the legacy of Vaclav Havel -or some such partisan drivel. Trevor-Roper would have seen through the ideologue Gershman, an American socialist youth leader, in an instant.

One way out of this would be to send them both to hell, and to choose the European (French) nuclear solution. But by far the most rational path to follow in this new, colder climate would be to remove the choice altogether.

Prague should give up its desire for more nuclear reactors, at least until tempers have cooled and rational considerations become possible again. It should come up with alternatives to large-scale nuclear generation projects, alternatives that do not involve the concentration of so much power in so few, foreign hands.

Alas, this most rational of options is becoming harder and harder to imagine these days: the Czech ruling class is epitomised by its president and industry minister, both of whom regard big as beautiful; if it is big and Russian, it is more beautiful still. These men do not have the finesse to choose between the Americans and the Russians in a way that would reduce the unavoidable political damage to the Czechs that will result from making the wrong choice -and there is only a wrong choice to be made.

There is a way out, and it is to follow the example of Germany. Berlin is a powerful neighbour and the single most valuable ally the Czech Republic could hope to have if it wanted to steer a middle course between the U.S. and Russia.

Ironically, Berlin also happens to be the one place Prague will never turn to for support in devising an energy policy that would allow it, politely, to dismiss both Washington and Moscow, and to abolish the nuclear new build option altogether.

The false choice before you today: American or Russian reactors?

In June 1950, 150 intellectuals from twenty countries gathered in West Berlin to take part in the ‘Congress for Cultural Freedom’, a CIA-funded response to the Communist-backed ‘Congress of the Intellectuals’ staged in the Polish city of Wroclaw two years earlier.

It was classic Cold War stuff. The English historian, Hugh Trevor-Roper, who participated in the Berlin congress, described it as ‘Wroclaw in reverse’. He stood out at the event for his point blank refusal to join in the partisan rant, dismissing the choice between embracing Communism and attacking it as not only false, but foolish as well: if European workers were forced to choose, he argued, they would likely choose Communism.

The ideological trampling upon rational debate is what alarmed Trevor-Roper most about those gatherings of anti-Communist intellectuals, many of them former Communists damaged by their pasts: "After the sterile congresses of Wroclaw and Berlin, I am confirmed in my view that a more satisfactory solution will be offered by those who have never swallowed, and therefore never needed to re-vomit, that obscurantist doctrinal rubbish whose residue can never be fully discharged from the system". (For an account of Trevor-Roper’s participation in the Berlin congress, see Adam Sisman’s biography of the man).

Today, as Washington and Moscow take up their old positions over Ukraine, rational debate is being crushed in the Czech Republic. By far the most significant illustration of this is the issue of who (not whether -that debate was never held here) will build more nuclear reactors in this country.

A year ago, there was still the possibility of making a rational choice between Rosatom and Westinghouse. But since Ukraine collapsed into a proxy war between Russia and the U.S., that possibility has disappeared.

There is no right choice now. It cannot be in the Czech interest to choose between Russia and the U.S. at this time, but if pushed, Prague will go for Rosatom. In either case, the Czechs would be mortgaging a large part of their politics, industry and national budget to one or other of the main combatants in the new Cold War. And in either case, the political fall-out would be considerable.

I can just hear Carl Gershman of the National Endowment for Democracy declaring that, by not choosing the Americans, the Czechs have abandoned the legacy of Vaclav Havel -or some such partisan drivel. Trevor-Roper would have seen through the ideologue Gershman, an American socialist youth leader, in an instant.

One way out of this would be to send them both to hell, and to choose the European (French) nuclear solution. But by far the most rational path to follow in this new, colder climate would be to remove the choice altogether.

Prague should give up its desire for more nuclear reactors, at least until tempers have cooled and rational considerations become possible again. It should come up with alternatives to large-scale nuclear generation projects, alternatives that do not involve the concentration of so much power in so few, foreign hands.

Alas, this most rational of options is becoming harder and harder to imagine these days: the Czech ruling class is epitomised by its president and industry minister, both of whom regard big as beautiful; if it is big and Russian, it is more beautiful still. These men do not have the finesse to choose between the Americans and the Russians in a way that would reduce the unavoidable political damage to the Czechs that will result from making the wrong choice -and there is only a wrong choice to be made.

There is a way out, and it is to follow the example of Germany. Berlin is a powerful neighbour and the single most valuable ally the Czech Republic could hope to have if it wanted to steer a middle course between the U.S. and Russia.

Ironically, Berlin also happens to be the one place Prague will never turn to for support in devising an energy policy that would allow it, politely, to dismiss both Washington and Moscow, and to abolish the nuclear new build option altogether.

Miluji cla! Donald Trump a jeho životní láska

Miluji cla! Donald Trump a jeho životní láska Finský prezident má recept na Trumpa. Golfovou diplomacii!

Finský prezident má recept na Trumpa. Golfovou diplomacii! Ukrajinská svatba online: rychlý válečný obřad bez příkras i bez příloh

Ukrajinská svatba online: rychlý válečný obřad bez příkras i bez příloh Z deníku dobrovolníka: Nebezpečná cesta za velitelkou Runou

Z deníku dobrovolníka: Nebezpečná cesta za velitelkou Runou Týden v Česku: Bendova pravda, Babišovo kafe a Pavlovo pózování

Týden v Česku: Bendova pravda, Babišovo kafe a Pavlovo pózování