Andrejko and his three really ugly sisters

Hold your nose if you must, but vote for a party, not a happy ending.

A happy ending

There are three kinds of voters (setting aside the loyalists). The first will be casting his vote for a political party he knows and deeply distrusts. This is the democratic condition, you might say.

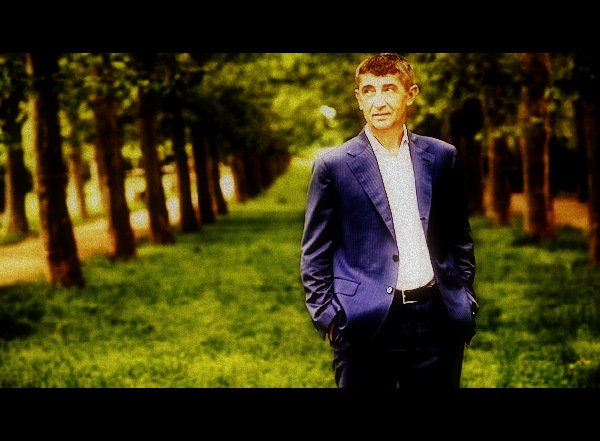

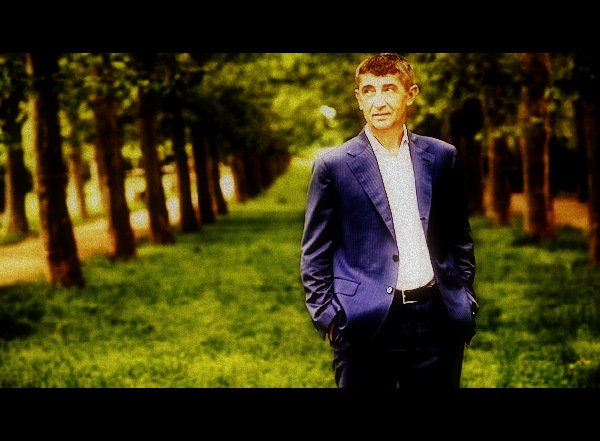

The second voter will make a giant leap of faith, and vote for Andrej Babis or one of his three, seriously ugly sisters - Jana Bobosikova, Tomio Okamura and Milos Zeman (dressed up as Martin Pecina or whichever Zemanite you fancy) - in the hope that a fairy tale prince (or princess in one case) can undo the damage done by a quarter of a century of free parliamentary elections. This is the politics of happy endings, you might say.

And the third kind of voter will not bother to vote at all.

All three voters would claim to be democrats but which of them is the better citizen? Is it the one who votes for a party he knows will cheat and steal? Or the one who votes for a charismatic leader he hopes will end all cheating and stealing? Or the one who washes his hands of them all, and goes mushrooming?

The mushroomer, that is to say the free citizen that chooses not to vote, does not relinquish his right to be heard. But he greatly reduces the chance that anyone will listen to what he has to say. He should move to Belarus, where the mushrooms are just as good.

The free citizen who longs for a happy ending poses the greatest threat to democracy. He votes for a charismatic leader, instead of a party, in an electoral system constructed around party competition (however feeble the competition, however corrupt the parties.) His frustration is understandable, but he has gravely misunderstood the nature of the democratic game.

And here we need to examine Andrej Babis, given that he is the most likely of all his ugly sisters to get into parliament next weekend. Babis might become a politician that fights for the common wealth. He might even set aside his own business interests.

Or he might not. Babis is fiercely pro-business, in the sense that he promotes his own business interests fiercely. But he is not pro-market, in the sense of promoting free and open competition.

You will argue that Babis is not the classic rent-seeker, living off economic privileges awarded by the state. You will say that he has created his own wealth. Perhaps, but he is also determined to protect that wealth by keeping competitors out.

I would prefer not to take Babis at his word. Many will object, arguing that the leaders of political parties are no more accountable than Andrej Babis. This might be true in practice. But the leaders of a party with well-defined and accepted internal democratic rules can, in principle, be held to account for their abuses.

Who or what will hold Babis to account for his abuses, apart from Andrej Babis himself?

The last type of voter is the democratic norm, the citizen that votes for a party he knows will disappoint. No leaps of faith are required when casting a vote for one of the four established parliamentary parties in this country. Their crimes have gone unpunished: they have not gone unnoticed.

The weaknesses of KDU-CSL and the Greens are known as well. But whatever the many failings of these six political parties, whether criminal or just petty, in each case their party structures and procedures are sufficiently robust to prevent a single person doing exactly as he pleases – even an individual as domineering and abusive as Miroslav Kalousek.

Their faults are collective, and must be solved collectively. There is no Gordian Knot to cut, and even if there was, Babis is no Alexander the Great.

One helpful way of thinking about the sheer folly of giving vast amounts of political power to Babis is to imagine for a moment that he is Kalousek without the constraints of a political party.

So hold your nose if you must, but vote for a political party, not a happy ending.

A happy ending

There are three kinds of voters (setting aside the loyalists). The first will be casting his vote for a political party he knows and deeply distrusts. This is the democratic condition, you might say.

The second voter will make a giant leap of faith, and vote for Andrej Babis or one of his three, seriously ugly sisters - Jana Bobosikova, Tomio Okamura and Milos Zeman (dressed up as Martin Pecina or whichever Zemanite you fancy) - in the hope that a fairy tale prince (or princess in one case) can undo the damage done by a quarter of a century of free parliamentary elections. This is the politics of happy endings, you might say.

And the third kind of voter will not bother to vote at all.

All three voters would claim to be democrats but which of them is the better citizen? Is it the one who votes for a party he knows will cheat and steal? Or the one who votes for a charismatic leader he hopes will end all cheating and stealing? Or the one who washes his hands of them all, and goes mushrooming?

The mushroomer, that is to say the free citizen that chooses not to vote, does not relinquish his right to be heard. But he greatly reduces the chance that anyone will listen to what he has to say. He should move to Belarus, where the mushrooms are just as good.

The free citizen who longs for a happy ending poses the greatest threat to democracy. He votes for a charismatic leader, instead of a party, in an electoral system constructed around party competition (however feeble the competition, however corrupt the parties.) His frustration is understandable, but he has gravely misunderstood the nature of the democratic game.

And here we need to examine Andrej Babis, given that he is the most likely of all his ugly sisters to get into parliament next weekend. Babis might become a politician that fights for the common wealth. He might even set aside his own business interests.

Or he might not. Babis is fiercely pro-business, in the sense that he promotes his own business interests fiercely. But he is not pro-market, in the sense of promoting free and open competition.

You will argue that Babis is not the classic rent-seeker, living off economic privileges awarded by the state. You will say that he has created his own wealth. Perhaps, but he is also determined to protect that wealth by keeping competitors out.

I would prefer not to take Babis at his word. Many will object, arguing that the leaders of political parties are no more accountable than Andrej Babis. This might be true in practice. But the leaders of a party with well-defined and accepted internal democratic rules can, in principle, be held to account for their abuses.

Who or what will hold Babis to account for his abuses, apart from Andrej Babis himself?

The last type of voter is the democratic norm, the citizen that votes for a party he knows will disappoint. No leaps of faith are required when casting a vote for one of the four established parliamentary parties in this country. Their crimes have gone unpunished: they have not gone unnoticed.

The weaknesses of KDU-CSL and the Greens are known as well. But whatever the many failings of these six political parties, whether criminal or just petty, in each case their party structures and procedures are sufficiently robust to prevent a single person doing exactly as he pleases – even an individual as domineering and abusive as Miroslav Kalousek.

Their faults are collective, and must be solved collectively. There is no Gordian Knot to cut, and even if there was, Babis is no Alexander the Great.

One helpful way of thinking about the sheer folly of giving vast amounts of political power to Babis is to imagine for a moment that he is Kalousek without the constraints of a political party.

So hold your nose if you must, but vote for a political party, not a happy ending.

Ideový guru Motoristů je Klaus. V desateru by mohli mít, že Rusko není nepřítel

Ideový guru Motoristů je Klaus. V desateru by mohli mít, že Rusko není nepřítel Hranolky ze sebe Fiala neudělá. Musí jezdit za voliči po celé zemi. Jinak je nezíská

Hranolky ze sebe Fiala neudělá. Musí jezdit za voliči po celé zemi. Jinak je nezíská Dětský sen

Dětský sen Stěhování s Hemingwayem

Stěhování s Hemingwayem Babiš vsadil na všeluxující taktiku. Potřebuje, aby lidé co nejméně přemýšleli

Babiš vsadil na všeluxující taktiku. Potřebuje, aby lidé co nejméně přemýšleli